Massive performance without headaches

The purpose of this blog post is to clear up some confusion about RESTEasy Reactive and answer some commonly asked questions around it.

消息确认

This blog post would not have been possible without the expert advice of Clement Escoffier and Stéphane Épardaud.

Imperative and Reactive: the elevator pitch

In our quest to understand why RESTEasy Reactive is important and how it differs from RESTEasy Classic, it helps to paraphrase a very important message that was first introduced here.

In general, Java web applications use imperative programming combined with blocking IO operations. This is incredibly popular because it is easier to reason about the code. Things get executed sequentially. When the application receives a request, the framework associates this request to a worker thread. When the request processing needs to interact with a database or another remote service, it relies on blocking IO. The thread is blocked waiting for the answer, making the communication synchronous. With this model one request is not affected by another as they are run on different threads. Even when one thread is waiting, other requests running on different threads are not slowed down significantly.

However, with this model, you need one thread for every concurrent request, which places a limit on the achievable concurrency. On the other side, the reactive execution model embraces asynchronous development models and non-blocking IO. With this model, multiple requests can be handled by the same thread. When the processing of a request can no longer make progress (because it requests a remote service, or interacts with a database for example), it uses non-blocking IO. Instead of blocking the thread, it schedules the operation and passes a continuation which would be invoked after the completion of the operation[1]. This releases the thread immediately, which can then be used to serve another request. When the result of the IO operation is available, the processing of the request is resumed and continues its execution.

This model enables the usage of a single IO thread to handle multiple requests. There are three significant benefits.

-

First, the response time is smaller because it does not have to jump to another thread.

-

Second, it reduces memory consumption as it decreases the usage of threads.

-

Third, your concurrency is no longer limited by the number of threads.

The reactive model uses the hardware resources more efficiently, but… a significant pitfall lurks. If the processing of a request starts to block, things can go south really quickly as no other request can be handled. To avoid this, you need to learn how to write asynchronous and non-blocking code, how to schedule operations, how to write continuations, how to chain actions. Basically, we need a way to structure asynchronous processing, and use non-blocking IO. No doubt, that consists of a paradigm shift. In Quarkus, we want to make the shift as easy as possible, so RESTEasy Reactive allows you to choose whether an endpoint is blocking or non-blocking (an application is free to mix and match blocking and non-blocking methods at will). So don’t be intimidated by the reactive word, the infrastructure is reactive, but your code can be either reactive or imperative. That’s what we mean by unification of reactive and imperative.

What that means from a RESTEasy Reactive perspective

RESTEasy Reactive by default handles each HTTP request on an IO thread (otherwise known as an event-loop thread)[2].

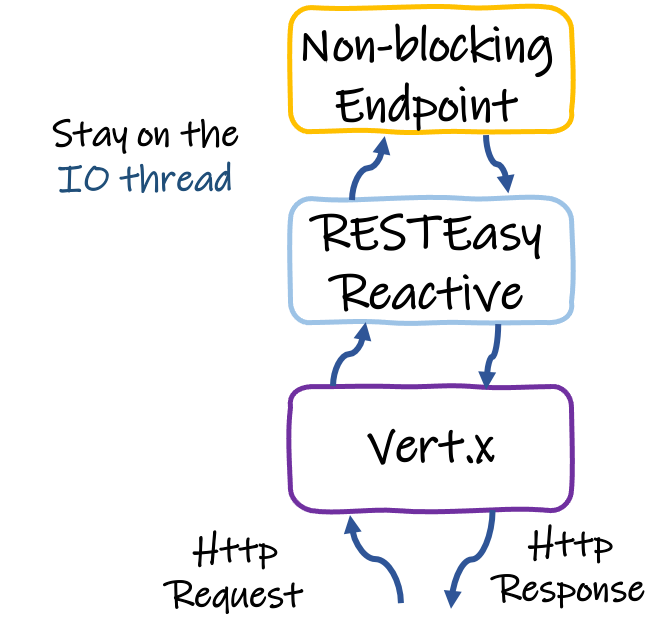

The following image shows what that looks at a high level:

This ensures that maximum throughput can be achieved, but it also means that the implementation of an endpoint method should complete in a timely fashion otherwise the thread will be used for too long[3] and other requests will be queued up and lead to degraded throughput.

It is important to understand that a method body that uses imperative code only becomes a problem when it takes a long time to execute - which is almost always the case for blocking IO operations.

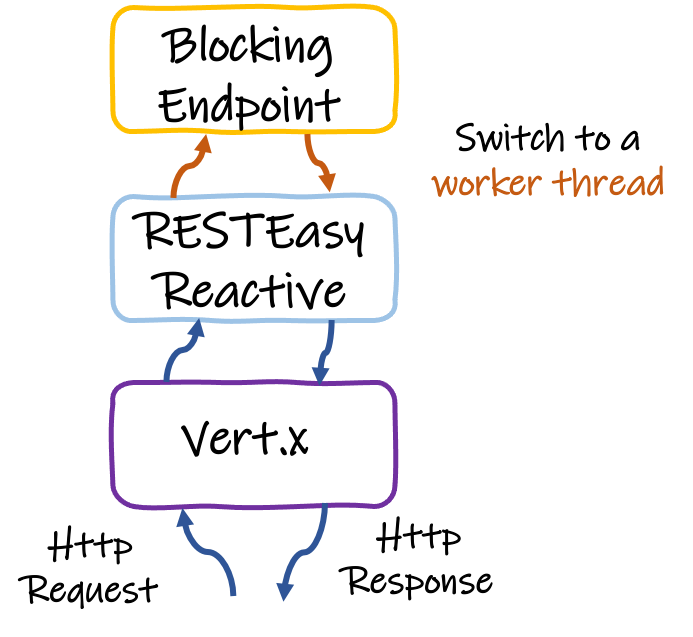

For that reason, when the body of the method performs some kind of blocking IO operation (or even some CPU bound operation that requires time to complete), the request needs to be offloaded to a worker thread.

In RESTEasy Reactive that is done declaratively using the @Blocking annotation - no reactive programming or complex Java concurrency related code is needed.

Quarkus also warns you when you attempt to use blocking IO on an IO thread.

If however the method body performs non-blocking IO (or some CPU bound operation that completes very quickly) then RESTEasy Reactive can continue to serve the entire request on the IO thread.

Is RESTEasy Reactive limited to using reactive APIs?

Absolutely not!

Although RESTEasy Reactive was built from the ground up to do non-blocking IO and serve requests from the event loop threads (thus avoiding the needless usage of worker pool threads) it can effortlessly work with blocking IO and any piece of code that provides a blocking API (such as Hibernate) without blocking the event loop.

The only thing you have to do is add @Blocking on your endpoint method or class.

That’s it! If you use @Blocking you are back to the regular dispatching mechanism: a worker thread is used to execute your method.

At a high level it this looks like this:

Does RESTEasy Reactive require Hibernate Reactive?

As you can probably guess from the answer to the previous question, the answer is no.

In scenarios where RESTEasy Reactive is used along with Hibernate, the @Blocking annotation should be placed on the endpoint methods that interact with Hibernate.

In scenarios where RESTEasy Reactive is used along with Hibernate Reactive, no @Blocking annotation is necessary on the endpoint methods that interact with Hibernate Reactive.

What is the performance implication of using @Blocking?

Although the absolute highest throughput is achieved when an endpoint method is non-blocking (that is the HTTP request is served completely from the event loop thread),

great performance can nonetheless be achieved even when @Blocking is used.

In our benchmarks we see the use of @Blocking reduce maximum throughput by around 30%[4].

However, an endpoint method using @Blocking in RESTEasy Reactive still achieves around 50% higher throughput than the same method using RESTEasy Classic.

Why does RESTEasy Reactive using @Blocking perform better than RESTEasy Classic?

RESTEasy Reactive is able to gain its performance advantage over RESTEasy Classic by:

-

Integrating very tightly with Eclipse Vert.x for everything IO related. Vert.x has been extremely well optimized for IO operations and so tight integration with it allows RESTEasy Reactive to benefit from all that work. You might recall that RESTEasy Classic on Quarkus uses Vert.x under the hood as well, but in that case the integration is not as deep and is therefore unable to fully utilize the power of Vert.x.

-

Moving a lot of work to build time. As RESTEasy Reactive was built from the ground up to serve the needs of Quarkus, it benefits from the tightest possible integration with Quarkus and is probably the extension that does the most build time work. This in turn results in creating an optimal data pipeline for serving each request, helping the JIT compiler by generating bytecode to inline runtime operations, eliminating reflection at runtime (both for invoking methods and for determining types) and reducing memory allocations.

-

Avoiding the use of ThreadLocals and instead by utilizing a context object that contains all the necessary information. ThreadLocals are a convenient way to make data available to different parts of a framework, but their frequent use comes at a cost and are thus fully avoided in RESTEasy Reactive.

-

Utilizing Arc in an optimal manner for all necessary injections. RESTEasy Classic provides an abstraction layer that performs the various injection operations, which for the needs of Quarkus is entirely unnecessary since Arc provides the same functionality with better performance.

How does it compare to RESTEasy Classic with Mutiny?

You might recall that Quarkus allows you to use Mutiny return types (Uni and Multi) when using RESTEasy Classic via the quarkus-resteasy-mutiny extension and thus might be wondering how that compares to using RESTEasy Reactive.

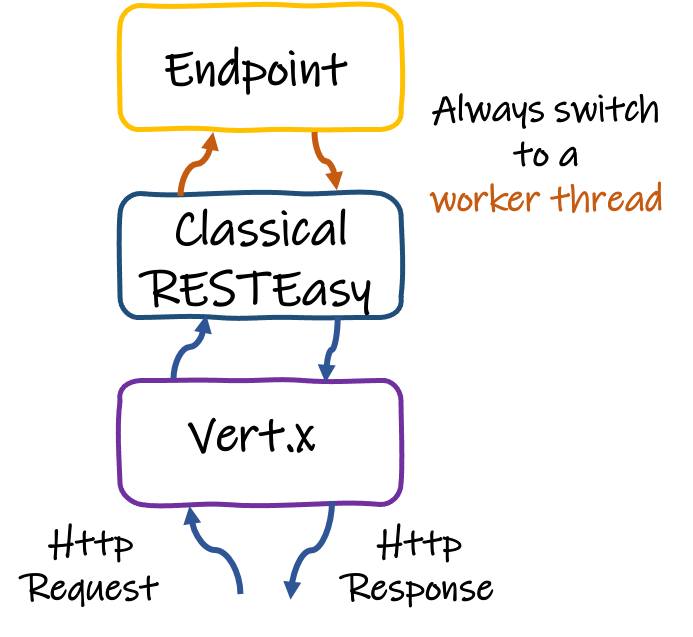

The main thing to understand about RESTEasy Classic is that it always handles requests on a worker thread as it does not use the event-loop concept at all.

This is best shown by the following image:

So when using RESTEasy Classic even when you return a reactive type like Uni or Multi the initial request is still being handled on a worker thread and while the call to the library may result in non-blocking IO,

nevertheless there is no way for RESTEasy Classic to reuse the worker thread once it is blocked waiting on IO.

Thus, the gain of using reactive return types in RESTEasy Classic is a syntactic gain, not a runtime gain - the underlying hardware isn’t used more efficiently despite the use of reactive types.

When returning Mutiny types using RESTEasy Reactive, everything happens on the IO Thread (except if the endpoint is annotated with @Blocking). By the way, no need for an external extension to use Mutiny with RESTEasy Reactive, it’s built-in!

Do I have to use the new RESTEasy Reactive APIs to achieve maximum performance?

Reading through the RESTEasy Reactive documentation you soon come across the new APIs for writing request filters (@ServerRequestFilter),

response filters (@ServerResponseFilter) and exception mappers (@ServerExceptionMapper).

You might wonder if their usage affects performance in any way compared to the standard JAX-RS APIs (ContainerRequestFilter, ContainerResponseFilter and ExceptionMapper).

Although the new APIs will give a tiny performance advantage over using the old APIs if the use of @Context is involved in the latter case, the advantage is negligible and should not worry you unless you are trying to squeeze out every inch of performance you can find.

One thing to keep in mind when writing filters with either API, is that using org.jboss.resteasy.reactive.server.SimpleResourceInfo instead of javax.ws.rs.container.ResourceInfo is advised as the latter results in reflection being performed.

A special (albeit rather advanced) case where the new APIs do result in noticeably better performance is the case of MessageBodyReader and MessageBodyWriter classes.

When reading the HTTP request and writing the HTTP response, the use of ServerMessageBodyReader and ServerMessageBodyWriter allows RESTEasy Reactive to optimize the data-path for serving the request.

What about Reactive Routes?

Quarkus was already providing a way to handle HTTP requests from the IO thread. Reactive Routes provides a declarative model to implement HTTP API. Each route can be called on the IO thread (default) or on a worker thread (using the @Blocking annotation).

Reactive Routes provide very good throughput and performance as highlighted in this article. How does reactive routes compare to RESTEasy Reactive?

One of the main complaints we got about Reactive Routes was about the development model: it’s very different from the one used with RESTEasy. However, Reactive Routes allowed us to verify the performance and efficiency benefits of using an end-to-end reactive model on top of Quarkus. RESTEasy Reactive can be seen as the “next generation”: you get the runtime benefits while also using a familiar development model.

Summary

RESTEasy Reactive is the next generation of HTTP framework. It unifies reactive (non-blocking IO, asynchronous APIs) and imperative (thanks to the @Blocking annotation). It improves raw performances without constraining the user experience.

Its reactive/imperative duality makes it fit any use cases, from highly concurrent HTTP APIs, to more traditional transactional CRUD applications.

We see RESTEasy Reactive as becoming the default HTTP layer in Quarkus in the near future and are completely committed to making it perform at the best possible level while also introducing new features that spark developer joy!

In that vein, we hope that this short blog post will provide you with some insight on what makes RESTEasy Reactive special and clear up any misconceptions you may have had about it.